The air we breathed:

a short history of Performance Magazine

By Lynn MacRitchie

In 2017, we can all be publishers, endlessly posting our thoughts into a virtual universe which may or may not take notice. But in 1979, when Performance Magazine was founded, it took a certain toughness – and an understanding printer willing to extend credit – to get the word out, literally, on to the streets. Toughness, and a conviction that there were things that had to be said, and that the time had come to say them. Rob La Frenais, founder and first editor of Performance Magazine, then working with Action Space transdisciplinary arts group in London, knew that something special was happening as the worlds in which he moved – theatre, art, dance, music, video – drew closer together. While the potential significance of this shifting artistic landscape was keenly felt by those involved, the conventional media remained oblivious, and Rob, originally trained as a journalist, decided to launch the publication he felt it deserved.

The response was immediate. From its very first issue, Performance Magazine became the place in which the emergent entity referred to as “performance” attempted to describe, define and analyse itself. Those “people who did odd things in front of others” (Rob’s definition of performance in Issue 1) and those who watched them had a lot to say and, in the new magazine, they had finally found a place to talk to each other.

This sense of urgency was compounded by the political climate of the times. The first issue was published in June 1979, one month after Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister, and the magazine ceased production in 1992, two years after her fall. Thus, its life as a publication was set entirely within a world shaped by a Conservative government bent on deconstructing state support for all sections of that society whose existence it denied, including cutting funding for the arts.

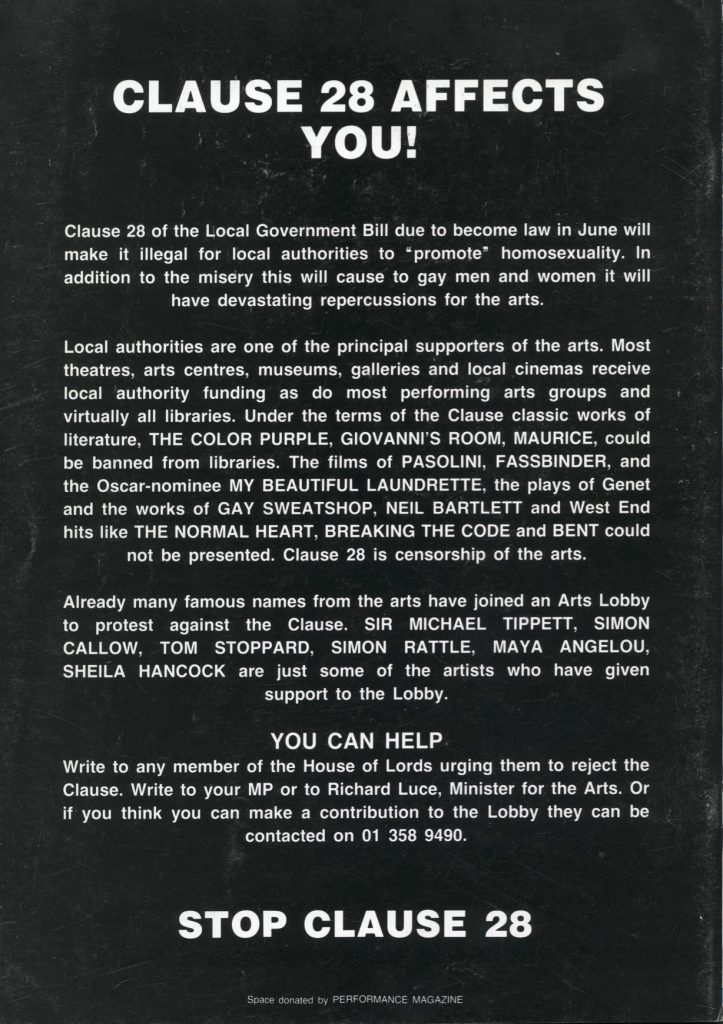

The magazine’s position was explicit. In “a clear triumph of capitalism and opportunism” it had to operate in a world run by “the worst set of Tories seen for centuries.” As Rob (who wrote the preceding quotes in Issue 4) puts it now, “You can’t be visible in the world (such as running an art magazine) without being political.” He was a Labour Party supporter, and contributors and subsequent editors were also of the left. “We were all affected in one way or another by Thatcherism and felt strongly about it…” he recalls. “It was the air we breathed.” For the personal, too, came under attack, with continuing attempts to restrict abortion rights and, most notoriously, with Clause 28, which banned the “promotion” of homosexuality in schools. From its earliest issues, the magazine was alert to the importance of the debates around sexual politics and regularly covered feminist, gay, lesbian and gender challenging work.

After eight years of publishing, however, things began to shift again. In issue 46 (March/April 1987) it was announced that Rob would be standing down as editor: having organised successful events at the Diorama and AIR Gallery, he had decided to work with artists rather than write about them. Long-standing contributor and Publishing Director Steve Rogers took charge as Managing Editor and each issue was given over to a different guest editor. This was a significant change in the ecology of the magazine. While it had had themed issues in the past, the guest editors – Chrissie Iles, Tracey Warr, Neil Bartlett, Claire MacDonald, Nik Houghton and Projects UK – inevitably brought their individual interpretation of “performance” to the editing function. Rob’s move into actual curation had thus brought the curatorial to the heart of the magazine itself, never more so than when what would have been Issue 55 became the catalogue for Edge 88, the international exhibition of performance he curated that year in London.

In a “news supplement” to that special edition, Steve Rogers, considering the latest proposed shift in Arts Council funding for the sector, made a heartfelt plea. What we need, he wrote, is “performance academics writing learned papers… access to reproductions of artists’ work… in photographs and videos… in the same way that access is available to reproductions of the paintings of Rembrandt”. In other words, it was time for performance, that unruly child, to grow up. It should no longer depend on the whims of funding fashions but must secure its future by defining its history, establishing the foundations of a performance canon to educate subsequent generations about the value and significance of such work.

Tragically, Steve was not to live to see the magazine take its own steps in just that direction. Having agreed that it would be relaunched as a quarterly, Steve died from AIDS-related pneumonia in December 1988, and that task fell to Gray Watson, who remained editor until the last issue of the magazine in spring 1992, when, ironically, his own burgeoning academic career made it impossible to continue. As Steve had hoped and Gray fulfilled, the quarterly format allowed the magazine to publish long form articles – on Fluxus, Situationism, Arte Povera and more – which situated performance within its own history. He also included writing on artists such as Jeff Koons, whose whole persona (and not just the sexual acts with porn star La Cicciolina he exhibited as photographs) could be considered a performance.

It all seems a very long way from the Kipper Kids and “Up Yer Bum”, the first article in Issue 1. But so it should be. As Gray Watson pointed out in his first editorial, the world – “both within capitalism and within communism, and with developments in sexual, racial and ecological politics”- had changed. And, while this had been happening, performance had fought its way, if not exactly to the heart of the art world, at least to a place where it was respected, funded, taught and above all taken seriously. And Performance Magazine, dedicated, staunch and unflinching, had been its companion every step of the way. It is surely a tribute to the prescience and persistence of all its contributors that, in 2017, while the magazine may be no more, for performance the art form the journey continues.